Teaching of Vocabulary

Teaching

word meanings should be a way for students to define their world, to move from

light to dark, to a more fine-grained description of the colors that surround

us.

—Steven Stahl

—Steven Stahl

A RATIONALE DIRECTLY ADDRESSING VOCABULARY DEVELOPMENT

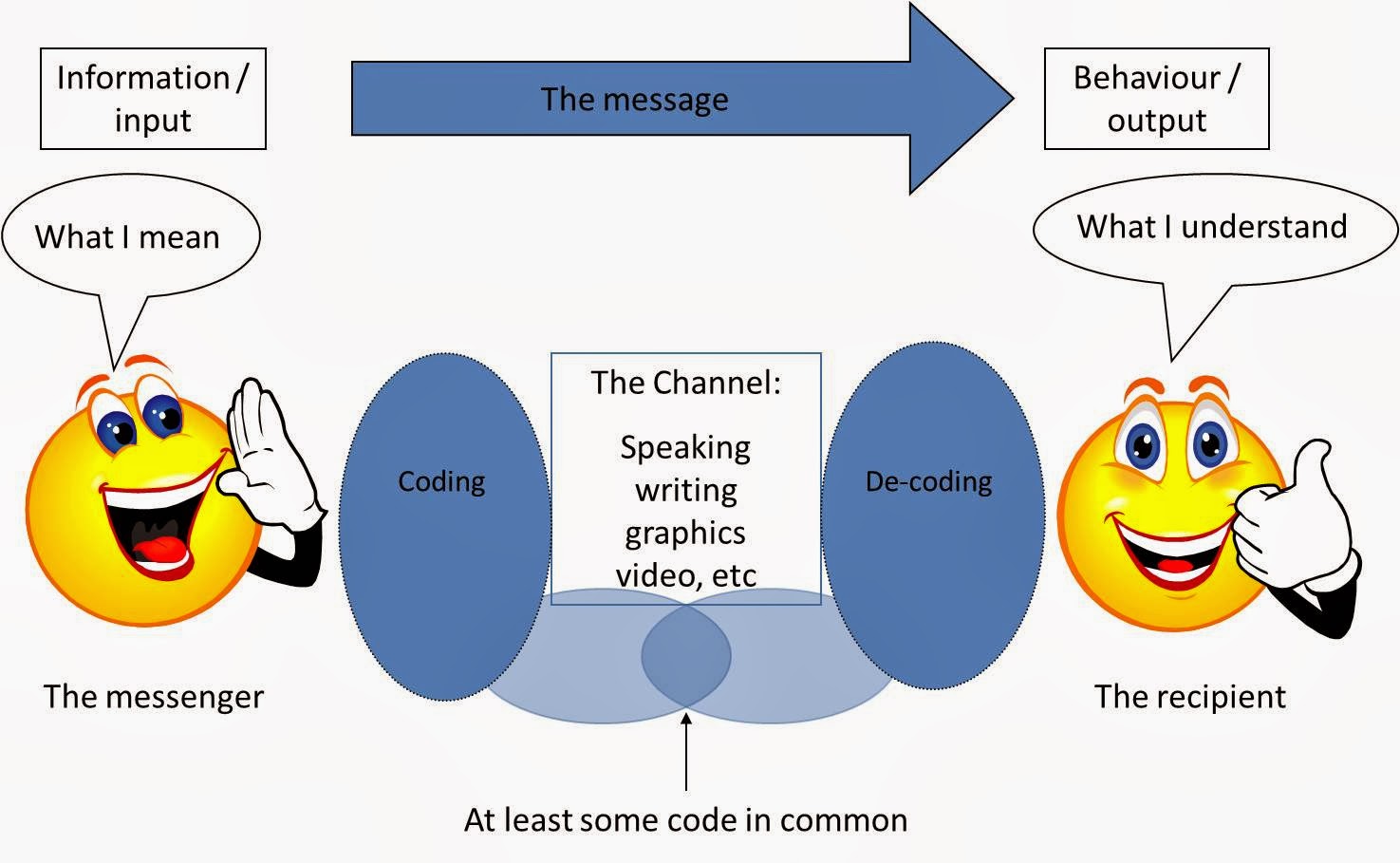

Successful comprehension is, in some significant part, dependent

on the reader's knowledge of word meanings in a given passage. Baker, Simmons,

and Kame'enui1state,

"The relation between reading comprehension and vocabulary knowledge is

strong and unequivocal. Although the causal direction of the relation is not

understood clearly, there is evidence that the relationship is largely

reciprocal." The good news for teachers from research in vocabulary development

is that vocabulary instruction does improve reading comprehension (Stahl2). However, not all approaches to

teaching word meanings improve comprehension. This chapter will describe some

of the most practical and effective strategies that high-school teachers can

employ with diverse learners to enhance vocabulary development and increase

reading comprehension.

WHAT DOESN'T WORK?

There are a number of traditional teaching practices related to

vocabulary that deserve to be left in the "instructional dustbin."

The key weakness in all of these practices is the limited or rote interaction

students have with the new word/concept. Let us quickly review the most common

of these less effective approaches.

1.

Look them

up. Certainly dictionaries have their place, especially during

writing, but the act of looking up a word and copying a definition is not

likely to resultin vocabulary

learning (especially if there are long lists of unrelated words to look up and

for which to copy the definitions).

2.

Use them in

a sentence. Writing sentences with new vocabulary

AFTER some understanding of the word is helpful; however to assign this task

before the study of word meaning is of little value.

3.

Use context. There is little research to suggest that context is a very

reliable source of learning word meanings. Nagy3 found that students reading

at grade level had about a one twentieth chance of learning the meaning of a

word from context. This, of course, is not to say that context is unimportant

but that students need a broader range of instructional guidance than the

exhortation "Use context."

4.

Memorize

definitions. Rote learning of word

meanings is likely to results, at best, in the ability to parrot back what is

not clearly understood.

The common shortcoming in all of these less effective approaches

is the lack of active student involvement in connecting the new concept/meaning

to their existing knowledge base. Vocabulary learning, like most other

learning, must be based on the learner's active engagement in constructing

understanding, not simply on passive re-presenting of information from a text

or lecture.

WHAT

DOES WORK?

Reviewing the research literature on vocabulary instruction

leads to the conclusion that there is no single best strategy to teach word

meanings but that all effective strategies require students to go beyond the

definitional and forge connections between the new and the known. Nagy3 summarizes

the research on effective vocabulary teaching as coming down to three critical

notions:

1.

Integration—connecting new vocabulary to prior knowledge

2.

Repetition—encountering/using the word/concept many times

3.

Meaningful

use—multiple opportunities to use new words in reading, writing and

soon discussion.

The following section will explore some practical strategies

that secondary teachers can employ to increase the integration, repetition, and

meaningful use of new vocabulary.

Increase the Amount of Independent Reading

The largest influence on students' vocabulary is the sheer

volume of reading they do, especially wide reading that includes a rich variety

of texts. This presents a particularly difficult challenge for underprepared

high-school students who lack the reading habit. The following strategies can

help motivate reluctant readers:

1.

Matching text difficulty to

student reading level and personal interests (e.g. using the Lexile system)

2.

Reading incentive programs

that include taking quizzes on books read (e.g., Accelerated Reader, Reading

Counts)

3.

Regular discussion, such as

literature circles, book clubs, quick reviews, of what students are reading

4.

Setting weekly/individual

goals for reading volume

5.

Adding more structure to

Sustained Silent Reading by including a 5-minute quick-write at the end of the

reading period, then randomly selecting three or four papers to read/grade to

increase student accountability.

Choose Appropriate Dictionaries for Heterogeneous Classrooms

Secondary students certainly need to know how and when to use a

dictionary to look up the meanings of unfamiliar words. Surprisingly, many

adolescents lack even the most rudimentary dictionary skills and benefit from

some explicit instruction. Without training and guidance, less proficient

readers and English language learners are apt to encounter numerous

difficulties as they struggle first to locate and then to effectively navigate

a lengthy dictionary entry.

Many students do not own a dictionary, and if they do, it is

often not a very powerful or appropriate resource for clarifying word meanings.

English learners may carry a bilingual dictionary, but this resource is

generally inadequate for several reasons. First, long-term bilinguals or more

recent immigrants with disrupted educational histories may have limited

academic vocabulary in the home language. When looking up the meaning of a term

such as categorize or stereotype, a

bilingual youth may very well encounter an unfamiliar word in the native

language. Simply copying a translation does little to promote reading

comprehension. Further, the small bilingual dictionaries carried by secondary

students offer limited and often inaccurate definitions. An electronic

dictionary may be equally unproductive for a bilingual or less proficient

reader tackling grade-level curricula, as it tends to offer scant definitions

and no contextualized example sentences. An electronic dictionary is useful for

a quick fix, but it is not the most considerate resource for a student operating

from a weak academic vocabulary base while completing grade-level assignments.

Another common language arts resource, which is likely to utterly demoralize an

under prepared reader, is an adult thesaurus. To benefit from an array of

synonyms, a reader must operate from a solid academic vocabulary base. Less

proficient English users will generally have no ability to gauge contextual

appropriateness and will end up infusing their written work with glaringly

inappropriate word choices.

A traditional collegiate dictionary is probably a less effective

resource for students daunted by grade-level literacy tasks. High school

classrooms are predictably equipped with only college-level dictionaries, which

are actually designed for a proficient adult reader possessing a relatively

sophisticated vocabulary base and efficient dictionary skills. This does not

describe the average high-school student, whether she or he is reading at or

below grade level. Collegiate dictionaries can be extremely frustrating

resources for most adolescent readers because they do not integrate the support

mechanisms of a "learners' dictionary."

Many publishers, including Longman and Heinle & Heinle, have

developed a line of manageable "learners' dictionaries" for secondary

students who need a more user-friendly dictionary to assist them in content

area coursework. A learner's dictionary characteristically includes fewer yet

more high-frequency definitions, written in accessible language and

complemented by an age-appropriate sample sentence. English language learners

and less proficient readers benefit from the clear, simple definitions and

common synonyms as much as from the natural examples illustrating words and

phrases in typical contexts. These dictionaries are also easier for students to

utilize than collegiate dictionaries because the entries are printed in a

larger type size and include useful and obvious signposts to guide them in

identifying the proper entry. A final advantage is that many learners'

dictionaries may be purchased in book form, along with a CD-ROM providing

pictures, audio, and pronunciation of headwords.

Developmentally-appropriate lexical resources are fundamental to

providing all students, regardless of their level of English proficiency or

literacy, with greater access to grade level competencies and curricula. A

democratic language arts classroom, marked by cultural and linguistic

diversity, must include considerately chosen and manageable dictionaries for

less proficient readers, to enable them to develop more learner autonomy and to

assist them in completing independent writing and reading tasks.

Select the Most Important Words to Teach

Students with weak lexical skills are likely to view all new

words as equally challenging and important, so it is imperative for the teacher

to point out those words that are truly vital to a secondary student's academic

vocabulary base. Unfortunately, teachers who gravitated toward English

instruction, in great part out of a passion for language and literature, may

find all words of equal merit and devote too much instructional time to

interesting and unusual, yet low-frequency, words, that a less prepared reader

is unlikely to encounter ever again. This lexical accessorizing is overwhelming

to a reader who may be striving simply to get the gist of a novel, and it

proves to be even more daunting as the student attempts to study a litany of

unfamiliar terms. Graves and Graves4 make a helpful distinction between

teaching vocabulary and teaching concepts. Teaching vocabulary is teaching new

labels / finer distinctions for familiar concepts. In contrast, teaching

concepts involves introducing students to new ideas / notions / theories / and

so on that require significantly more instruction to build real understanding.

Teachers can get more out of direct vocabulary work by selecting words

carefully. More time-consuming and complex strategies are best saved for

conceptually challenging words, while relatively expedient strategies can

assist students in learning new labels or drawing finer-grained distinctions

around known concepts. Making wise choices about which words to teach directly,

how much time to take, and when enough is enough is essential to vocabulary

building.

Tips for selecting words:

1.

Distinguish between words

that simply label concepts students know and new words that represent new

concepts.

2.

Ask yourself, "Is this

concept / word generative? Will knowing it lead

to important learning in other lessons / texts / units?"

3.

Be cautious to not

"accessorize" vocabulary (e.g., spend too much time going over many

clever adjectives that are very story specific and not likely to occur

frequently). Rather, focus attention on critical academic vocabulary that is

essential to understanding the big ideas in a text (e.g., prejudicial: As

students learn the meanings of pre- and judge, they can connect to other concepts they know, such as

"unfair.")

Brief Strategies for Vocabulary Development (Stahl5)

Words that are new to students but represent familiar concepts

can be addressed using a number of relatively quick instructional tactics. Many

of these (e.g., synonyms, antonyms, examples) are optimal for prereading and

oral reading, which call for more expedient approaches.

1.

Teach

synonyms. Provide a synonym students know, (e.g.,

link stringent to the

known word strict).

2.

Teach

antonyms. Not all words have antonyms, but

thinking about for those that do, opposite requires their students to evaluate

the critical attributes of the words in question.

3.

Paraphrase

definitions. Requiring students to use

their own words increases connection making and provides the teacher with

useful informal assessment—"Do they really get it?"

4.

Provide

examples. The more personalized the better. An

example for the new word egregious might be Ms. Kinsella's 110-page reading assignment was egregious indeed!

5.

Provide

nonexamples. Similar to using antonyms,

providing non-examples requires students to evaluate a word's attributes.

Invite students to explain why it is not an example.

6.

Ask for

sentences that "show you know." Students

construct novel sentences confirming their understanding of a new word, using

more than one new word per sentence to show that connections can also be

useful.

7.

Teach word

sorting. Provide a list of vocabulary words from

a reading selection and have students sort them into various categories (e.g.,

parts of speech, branches of government). Students can re-sort words into

"guess my sort" using categories of their own choosing.

STRATEGIES FOR CONCEPTUALLY CHALLENGING WORDS

Selecting and teaching conceptually demanding words is essential

to ensuring that diverse learners are able to grapple with the "big

ideas" crucial to understanding a challenging text. Complex concepts

require more multidimensional teaching strategies. The next section will

elaborate on a number of these techniques: list-group-label, possible

sentences, word analysis (affixes and roots), and concept mapping.

List-Group-Label

This is a form of structured brainstorming designed to help

students identify what they know about a concept and the words related to the

concept while provoking a degree of analysis and critical thinking. These are

the directions to students:

1.

Think of all the words

related to ______. (a key "big idea" in the text)

2.

Group the words listed by

some shared characteristics or commonalties.

3.

Decide on a label for each

group.

4.

Try to add words to the

categories on the organized lists.

Working in small groups or pairs, each group shares with the

class its method of categorization and the thinking behind its choices, while

adding words from other class members. Teachers can extend this activity by

having students convert their organized concepts into a Semantic Map which a

visual expression of their thinking.

List-group-label is an excellent prereading activity to build on

prior knowledge, introduce critical concepts, and ensure attention during

selection reading.

Possible Sentences (Moore and Moore7)

This is a relatively simple strategy for teaching word meanings

and generating considerable class discussion.

1.

The teacher chooses six to

eight words from the text that may pose difficulty for students. These words

are usually key concepts in the text.

2.

Next, the teacher chooses

four to six words that students are more likely to know something about.

3.

The list of ten to twelve

words is put on the chalk board or overhead projector. The teacher provides

brief definitions as needed.

4.

Students are challenged to

devise sentences that contain two or more words from the list.

5.

All sentences that students

come up with, both accurate and inaccurate, are listed and discussed.

6.

Students now read the

selection.

7.

After reading, revisit the

Possible Sentences and discuss whether they could be true based on the passage

or how they could be modified to true.

Stahl8 reported that Possible Sentences

significantly improved both students' overall recall of word meanings and their

comprehension of text containing those words. Interestingly, this was true when

compared to a control group and when compared to Semantic Mapping.

Word Analysis / Teaching Word Parts

Many underprepared readers lack basic knowledge of word origins

or etymology, such as Latin and Greek roots, as well as discrete understanding

of how a prefix or suffix can alter the meaning of a word. Learning clusters of

words that share a common origin can help students understand content-area

texts and connect new words to those already known. For example, a secondary

teacher (Allen9)

reported reading about a character who suffered from amnesia. Teaching students

that the prefix a– derives

from Greek and means "not," while the base mne– means "memory" reveals the

meaning. After judicious teacher scaffolding, students were making connections

to various words in which the prefix a– changed

the meaning of a base word (e.g., amoral, atypical). This type of

contextualized direct teaching meets the immediate need of understanding an

unknown word while building generative knowledge that supports students in

figuring out difficult words in future reading.

Learning and reviewing high frequency affixes will equip

students with some basic tools for word analysis, which will be especially

useful when they are prompted to apply them in rich and varied learning

contexts. The charts below summarize some of the affixes worth considering

depending on your students' prior knowledge and English proficiency.

|

Prefix

|

Meaning

|

% of All

Prefixed Words |

Example

|

|

un

|

not;

reversal of

|

26

|

uncover

|

|

re

|

again,

back, really

|

14

|

review

|

|

in / im

|

in,

into, not

|

11

|

insert

|

|

dis

|

away,

apart, negative

|

7

|

discover

|

|

en / em

|

in;

within; on

|

4

|

entail

|

|

mis

|

wrong

|

3

|

mistaken

|

|

pre

|

before

|

3

|

prevent

|

|

a

|

not;

in, on; without

|

1

|

atypical

|

Similarly, a quick look at the most common suffixes reveals a

comparable pattern of relatively few suffixes accounting for a large percentage

of suffixed words.

|

Suffix

|

Meaning

|

% of All

Suffixed Words |

Example

|

|

-s, -es

|

more

than one; verb marker

|

31

|

characters,

reads, reaches

|

|

-ed

|

in

the past; quality, state

|

20

|

walked

|

|

-ing

|

when

you do something; quality, state

|

14

|

walking

|

|

-ly

|

how

something is

|

7

|

safely

|

|

-er, -or

|

one

who, what, that, which

|

4

|

drummer

|

|

-tion, -sion

|

state,

quality; act

|

4

|

action,

mission

|

|

-able, -ible

|

able

to be

|

2

|

disposable,

reversible

|

|

-al, -ial

|

related

to, like

|

1

|

final,

partial

|

There are far too many affixes to directly teach them all;

however, it is important to realize that relatively few affixes account for the

majority of affixed words in English. Thus, it is helpful to explicitly teach

high-utility affixes (meaning and pronunciation) and assist students in making

connections as they encounter new vocabulary containing these parts. Once these

basic affixes have been mastered, it can be useful to explore more complex or

less frequent word parts, such as the following:

|

Prefixes

|

Meaning

|

Example

|

|

multi-

|

many

|

multimedia

|

|

pan-

|

all

|

pandemic,

Pan-American

|

|

micro-

|

very

small

|

microcosm

|

|

pro-

|

in

favor of, before

|

protect

|

|

Suffixes

|

|

|

|

-less

|

without;

not

|

useless

|

|

-ism

|

state,

quality; act

|

realism

|

Additionally, focused word study that builds student knowledge

of Greek and Latin roots, or bases, can be of significant assistance to

secondary students. Diverse learners in particular, are unlikely to have read

enough or engaged in enough academic conversations beyond school in which key

roots were clarified. Linguists estimate that well over 50 percent of

polysyllabic words found in English texts are of Latin or Greek derivation,

underlining the importance of ensuring that students learn "English from

the roots up."

Common Latin and Greek Roots (Stahl)

|

Root

|

Meaning

|

Origin

|

Examples

|

|

-aud-

|

hear

|

Latin

|

audio,

audition

|

|

-astro-

|

star

|

Greek

|

astrology,

astronaut

|

|

-bio-

|

life

|

Greek

|

biography,

biology

|

|

-dict-

|

speak,

tell

|

Latin

|

dictate,

predict

|

|

-geo-

|

earth

|

Greek

|

geology,

geography

|

|

-meter-

|

measure

|

Greek

|

thermometer

|

|

-min-

|

small,

little

|

Latin

|

minimize,

minimum

|

|

-port-

|

carry

|

Latin

|

transport,

portable

|

|

-phono-

|

sound

|

Greek

|

microphone

|

|

-duc(t)-

|

lead

|

Latin

|

deduct,

produce, educate

|

Tips for Word Study of Latin and Greek Roots

1.

Highlight Greek and Latin

roots as they come up in your readings—briefly for less important words and in

more depth for essential concepts.

2.

Associate the new word

derived from a root with more generally known words in the students' lexicon.

Visual organizers can be helpful.

3.

Encourage students to look

for additional words that share the newly learned root in their independent

reading and reading in other content classes.

4.

Encourage students to use

words containing newly learned roots in their writing, conversations, or

discussions.

Concept Mapping/Clarifying Routine

Research by Frayer et al. supports the strategy of teaching

concepts by

1.

identifying the critical

attributes of the word.

2.

giving the category to which

the word belongs.

3.

discussing examples of the

concept.

4.

discussing nonexamples.

Others have had success extending this approach by guiding

students through representation of the concept in a visual map or graphic

organizer. The Clarifying Routine, designed and researched by Ellis et al.,13 is a

particularly effective example of concept mapping. These are the steps:

1.

Select a critical concept /

word to teach. Enter it on a graphic clarifying map like the sample for satire.

2.

List the clarifiers or

critical attributes that explicate the concept.

3.

List the core idea—a summary

statement or brief definition.

4.

Brainstorm for knowledge

connections—personal links from students' word views/prior knowledge (encourage

idiosyncratic / personal links).

5.

Give an example of the

concept; link to clarifiers: "Why is this an example of ___?"

6.

Give nonexamples. List

nonexamples: "How do you know ___ is not an example of ___?"

7.

Construct a sentence that

"shows you know."

|

Term: SATIRE

|

||

|

Core Idea: Any Work That Uses Wit to Attack Foolishness

|

||

|

Example

A story that exposes the acts of corrupt politicians by making fun of them Nonexample A story that exposes the acts of corrupt politicians through factual reporting Example sentence Charles Dickens used satire to expose the problems of common folks in working-class England. |

Clarifiers

• Can be oral or written. • Ridicule or expose vice in a clever way. • Can include irony exaggeration, name-calling, understatement. • Are usually based on a real person or event. |

Knowledge Connections

• Political cartoons on the editorial pages of our paper. • Stories TV comics tell to make fun of the President—like Saturday Night Live. • My mom's humor at dinner time! |

Tips for

Using the Clarifying Routine

1.

Provide all students with a

blank clarifying map, and guide them in filling it out while you model your

thinking on an overhead projector.

2.

In the "knowledge

connections" (step 4 above), encourage students to generate their own

idiosyncratic links—anything to remind them of the concept. Total accuracy is

not as important as forging the cognitive linkage to the core idea.

3.

Focus on nonexamples. This

challenges students to explicate "why ___ is not an example of ___."

This level of analysis will greatly assist understanding.

4.

Vary use of the routine as

students become familiar with the steps, turning more and more of the process

over to student direction / control; for example, providing students with a

partially-filled-in map if their prior knowledge or proficiency in English

requires more support.

5.

Challenge students to fill

out their own clarifying maps.

AUTHENTIC ASSESSMENT OF VOCABULARY MASTERY

Because vocabulary plays such a central role in English language

arts instruction, it makes sense to assess students' comprehension and mastery

of essential words and phrases introduced during the course of a unit or

lesson. However, so much new vocabulary may be highlighted in any given lesson that

it makes sense to prioritize words for students and to clearly stipulate those

that are most important and that you intend to include in an assessment.

During language arts instruction and assessment, it is helpful

to make a distinction between words that should simply enhance a student's receptive vocabulary and words that should ideally

enter a student's expressive vocabulary.

A student's receptive vocabulary comprises to words that are recognized and

understood if presented in a rich and meaningful context when he or she is

listening or reading. This does not mean that the student necessarily feels

comfortable using words in either conversation or writing. A student's actual

expressive vocabulary is those words that the individual can use both confidently

and appropriately. When designing vocabulary assessments, it seems reasonable

to include a majority of foundational words that are truly critical to a

student's grade level academic lexicon—more high-frequency terms that the

learners are likely to encounter both within and outside of the language arts

classroom as they progress in their schooling.

Traditional vocabulary assessments can reveal little about a

student's actual word mastery, particularly those assessments that require

simple matching, a written definition, or use of the word in an original

sentence. While a student may be able to recall a memorized definition and an

example sentence provided by the dictionary or the instructor, there is no

guarantee that the student can actually use the word with facility. Many

students have refined their skills in rote memorization and succeed with these

rote-level assessments. Then a week later they proceed to misapply the terms in

the next writing assignment. For this reason, teachers should refrain from

designing quizzes that merely tap into students' short-term memorization and

should instead require critical thinking and creative application.

There are many ways to design more authentic vocabulary

assessments. Following are three meaningful and alternative assessment formats

that require relatively little preparation time:

Assessment Formats

1.

Select only four to six

important words and embed each in an accessible and contextualized sentence

followed by a semicolon. Ask students to add another sentence after the

semicolon that clearly demonstrates their understanding of the italicized word

as it is used in this context. This assessment format will discourage students

from rote memorization and merely recycling a sample sentence covered during a

lesson.

Example: Mr. Lamont had the most eclectic wardrobe of any teacher on the high-school staff;

Example: Mr. Lamont had the most eclectic wardrobe of any teacher on the high-school staff;

2.

Present four to six sentences

each containing an italicized word from the study list and ask students to

decide whether each word makes sense in this context. If yes, the student must

justify why the sentence makes sense. If no, the student must explain why it is

illogical, and change the part of the sentence that doesn't make sense.

Example: Mr. Lamont had the most eclectic wardrobe of any teacher on the high-school staff; rain or shine, he wore the same predictable brown loafers, a pair of black or brown pants, a white shirt, and a beige sweater vest.

Example: Mr. Lamont had the most eclectic wardrobe of any teacher on the high-school staff; rain or shine, he wore the same predictable brown loafers, a pair of black or brown pants, a white shirt, and a beige sweater vest.

3.

Write a relatively brief

passage (one detailed paragraph) that includes six to ten words from the study

list. Then, delete these words and leave blanks for students to complete. This

modified cloze assessment will force students to scrutinize the context and

draw upon a deeper understanding of the words' meanings. Advise students to

first read the entire passage and to then complete the blanks by drawing from

their study list. As an incentive for students to prepare study cards or more

detailed notes, they can be permitted to use these personal references during

the quiz (particularly if you have designed a more challenging passage).

Because these qualitative and authentic assessments require more rigorous analysis and application than most objective test formats, it seems fair to allow students to first practice with the format as a class exercise and even complete occasional tests in a cooperative group. Another suggestion is to frequently assign brief vocabulary quizzes rather than occasionally assign expansive tests, to encourage students to review vocabulary regularly and to facilitate transfer to long-term memory.

Because these qualitative and authentic assessments require more rigorous analysis and application than most objective test formats, it seems fair to allow students to first practice with the format as a class exercise and even complete occasional tests in a cooperative group. Another suggestion is to frequently assign brief vocabulary quizzes rather than occasionally assign expansive tests, to encourage students to review vocabulary regularly and to facilitate transfer to long-term memory.

SUMMARY

In sum, there are countless additional strategies that teachers

can employ to assist students in building their vocabularies. However, it is

essential to keep in mind that promoting extensive reading, carefully selecting

which words to teach quickly and which to teach extensively, and choosing

strategies that help students make cognitive connections between the new and

the known are at the heart of effective vocabulary building. Last, the more

intangible notion of taking delight in the world of words, modeling one's own

love of language, pushing the "lexical envelope" is less subject to research

study but nonetheless certainly worthy of consideration.

REFERENCES

Allen, J. Words, Words, Words: Teaching Vocabulary in Grades 4–12.

York, ME: Stenhouse 1999.

Baker, S. K., D. C. Simmons, and E. J. Kame'enui.

"Vocabulary acquistion: Instructional and curricular basics and

implications." In D. C. Simmons and E. J. Kame'enui (eds.), What

Reading Research Tells Us About Children With Diverse Learning Needs.

Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988, pp. 219–238.

Ellis, E. (1997). The Clarifying Routine. Lawrence, KS: Edge

Enterprises 1997.

Graves, M. and Graves, B. Scaffolding Reading Experiences: Designs for Student Success.

Norwood, MA.: Christopher Gordon 1994.

Moore, P. W. and S. A. Moore. "Possible sentences." In

E. K. Dishner, T. W. Bean, J. E. Readence, and P. W. Moore (eds.), Reading in

the Content Areas: Improving Classroom Instruction, 2nd ed.,1986. Dubuque, IA:

Kendall/Hunt pp. 174–179.

Nagy, W. Teaching Vocabulary to Improve Reading Comprehension.

Newark, DE: International Reading Association 1988.

Stahl, S. A. Vocabulary Development. Cambridge, MA:

Brookline Books 1999.

Taba, H. Teacher's Handbook for Elementary Social Studies.

Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley 1967.

Source http://www.phschool.com/eteach/language_arts/2002_03/essay.html

Comments

Post a Comment