Communication: Meaning & Importance

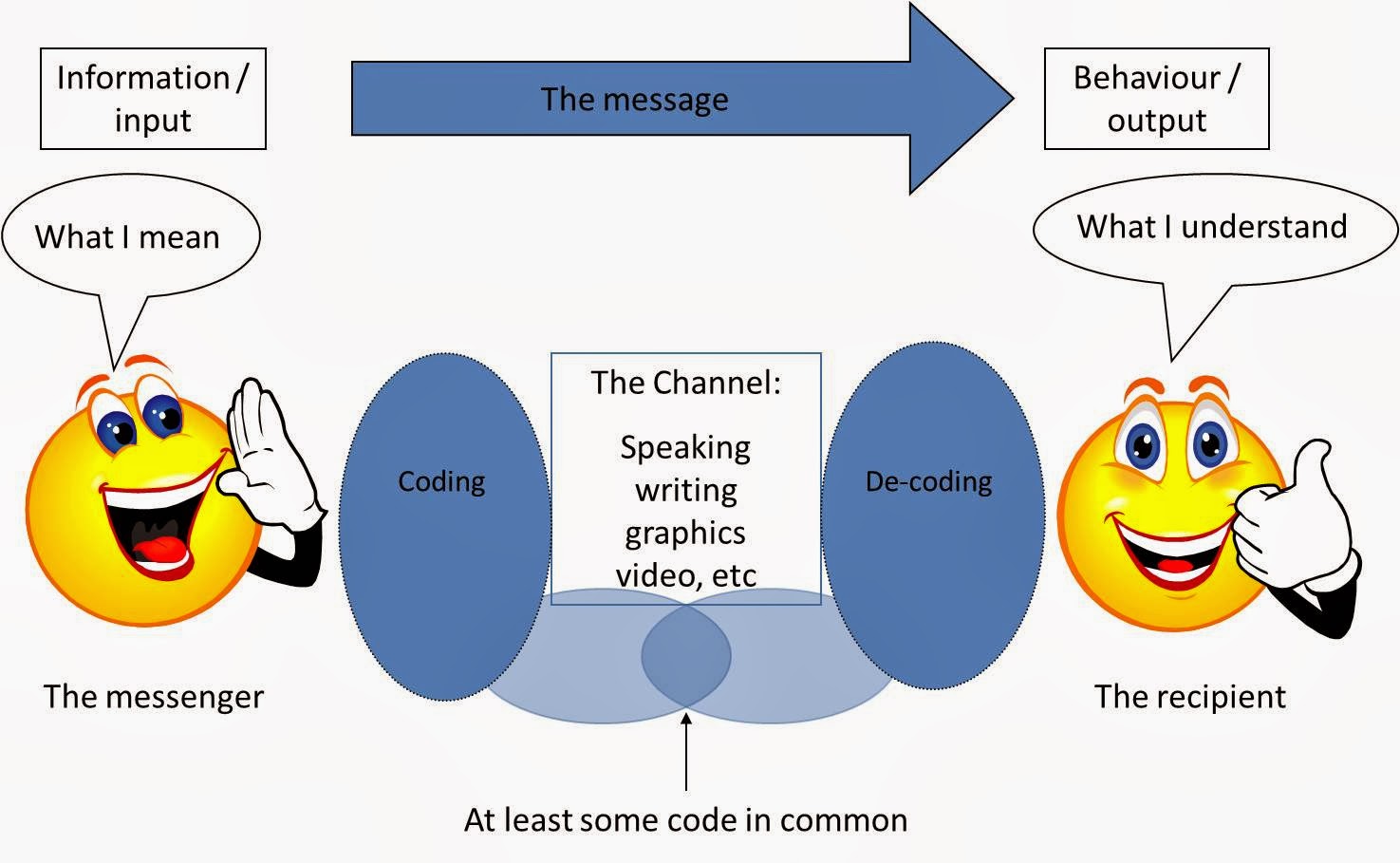

Communication comes from the Latin word 'Communicare', which means to make familiar or to share. The root definition of communication: communication means the process of using a message to generate meaning. Here understanding emerges from shared meaning. Understanding the importance of another person's message does not occur unless the two communicators can elicit common meanings for words, phrases, and non-verbal cues.

IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNICATION IN HUMAN LIFE

Humans have a fundamental, powerful, and universal desire to interact with others. There is a long history of research establishing the importance that individuals place on connectedness .. . individuals' needs for initiating, developing and maintaining social ties, especially close ones, is reflected in a litany of studies and a host of theories (Afifi and Guerrero, 2000). The mere presence of another is arousing and motivating, which, in turn, influences our behaviour – a process termed compresence (Burgoon et al.,1996). We behave differently in the company of another person than when alone. When we meet others, we are 'onstage' and give a performance that differs from how we behave 'offstage'.

We also enjoy interacting, and engaging in facilitative interpersonal communication has been shown to contribute to positive changes in emotional state (Gable and Shean, 2000). While our dealings with others can sometimes be problematic or even contentious, we also seek, relish and obtain a great reward from social interaction. Conversely, if we cannot engage meaningfully with others or are ostracised by them, the result is often loneliness, unhappiness, and depression (Williams and Zadiro,2001). The seemingly innate need for relationships with others has been termed association (Wolff,1950). Across time and settings, people everywhere have subscribed to the view that close, meaningful ties to others are an essential feature of being fully human (Ryff and Singer, 2000).

In other words, individuals need to commune with others. Three core psychological needs have been identified – competence, relatedness, and autonomy – and the satisfaction of all three results in optimal well-being (Patrick et al.,2007).

1] The competence need involves a wish to feel confident and efficient in carrying out actions to achieve one's goals.

2] The relatedness requirement reflects a desire to have close connections and positive relationships with significant others.

3] The autonomy need involves wanting to feel in control of one's destiny rather than being directed by others.

To satisfy all three psychological needs, it is necessary to have an effective repertoire of interpersonal skills. These skills have always been critical.

Levinson (2006) argued that the human mind is specifically adapted to enable us to engage in social interaction and that we could be more accurately referred to as homo interagens.

Another reason for sociation is that: 'The essence of communication is the formation and expression of identity. The formation of the self is not an independent event generated by an autonomous actor. Rather, the self emerges through social interaction' (Coover and Murphy, 2000: 125). This creates a sense of personal identity through negotiation with others (Postmes et al.,2006: 226). In other words, individuals become the people they are due to their interchanges with others. Interaction is an essential nutrient that nourishes and sustains the social milieu.

Furthermore, since communication is a prerequisite for learning, without the capacity for sophisticated methods and channels for sharing knowledge, both within and between generations, our advanced human civilization would just not exist. Communication, therefore, represents the very essence of the human condition. Indeed, one of the harshest punishments available within most penal systems is solitary confinement – the removal of any possibility of interpersonal contact. Thus, people have a deep-seated need to communicate, and the greater their ability in this regard, the more satisfying and rewarding their existence will be.

Research has shown that those with higher levels of interpersonal skills have many advantages in life (Burleson, 2007; Segrin and Taylor, 2007; Segrin et al.,2007; Hybels and Weaver, 2009). They cope more readily with stress, adapt and adjust better to significant life transitions, have higher self-efficacy in social situations, have greater satisfaction in their close personal relationships, have more friends, and are less likely to suffer depression, loneliness or anxiety. One reason for this is that they are sensitive to other people's needs, which leads to them being liked by others, who will seek out their company.

REWARDS FOR EXCELLENT COMMUNICATION SKILLS

In a review of research, Segrin (2000) concluded that interactive skills have a 'prophylactic effect' in that socially competent people are resilient to the ill effects of life crises. In contrast, individuals with poor skills experience worsening psychosocial problems when faced with stressors in life. Segrin and Taylor (2007: 645) summarise: 'Human beings seek and desire quality interpersonal relationships and experiences. Social skills appear to be a primary mechanism for acquiring such relationships, and where they are experienced, visible signs of positive psychological status abundantly evident.' Many of the benefits here are, of course, interrelated. So it is probable that the network of friendships developed by skilled individuals helps to buffer and support them in times of personal trauma. Those with high skill levels also act as active communication role models for others and are more likely to be effective parents, colleagues or teachers.

Other tangible rewards can be gained from developing an effective communication skill repertoire. These begin from an early age since children who develop good interactive skills also perform better academically (McClelland et al.,2006; Graziano et al.,2007). Skilled children know how to communicate effectively with the teacher and are more likely to receive help and attention in the classroom. Their interactive flair also enables them to develop peer friendships, making school a more enjoyable experience. The benefits then continue in many walks of life after school. In the business sphere, there are considerable advantages to be gained from good communication (Robbins and Judge, 2009), and efficient managers have been shown to have a strong repertoire of interpersonal skills (Bambacas and Patrickson, 2008; Clampitt, 2010). Surveys of employers also consistently show that they rate the ability to communicate effectively as a critical criterion in recruiting new staff (CBI, 2008).

Entrepreneurs with high levels of interpersonal skills have advantages in various areas, such as obtaining funding, attracting quality employees, maintaining healthy relationships with co-founders of the business, and producing better results from customers and suppliers (Baum et al.,2006). Not surprisingly, skilled communicators are upwardly mobile and more likely to receive pay raises and promotions (Burleson, 2007). Likewise, in healthcare, the importance for professionals of having a 'good bedside manner' has long been realized. In 400 BC, Hippocrates noted how the patient 'might recover his health simply through his contentment with the goodness of the physician'. In recent years, this belief in the power of communication to contribute to the healing process has been borne out by research. Di Blasi et al. (2001) conducted a systematic review of studies in Europe, the USA, and Canada that investigated the effects of doctor-patient relationships. They found that practitioner interpersonal skills made a significant difference in patient well-being. Professionals with excellent interpersonal skills formed a warm, friendly relationships with their patients and provided reassurance. They were more efficient regarding patient well-being than those who kept consultations impersonal or formal. Thus, in teaching, interpersonal skills are critical for optimum classroom performance (Worley et al.,2007).

As aptly summarised by Orbe and Bruess (2005): 'The quality of our communication and the quality of our lives are directly related. Our lives are a direct reflection of the quality of the communication in them.' Communication skills are at the very epicentre of our social existence, and humans ignore them at their peril. However, the good news is that they can improve their communication ability.

Much is now known about the critical constituents of the DNA interactive life. Given the early historical focus on communication, it is perhaps surprising that this area was subsequently largely neglected regarding academic study in higher education until its resurgence in the late twentieth century. Bull (2002: vii) noted: 'Communication is of central importance to many aspects of human life, yet it is only in recent years that it has become the focus of the scientific investigation.' For example, it was not until 1960 that the notion of communication as a form of skilled activity was first suggested (Hargie, 2006a).

Comments

Post a Comment